Poet, novelist, and critic Michael Meyehofer (poetry editor at Atticus Review) shows some love to Brackish in the new issue of Rain Taxi. I am very appreciative of this insightful review. I'm a huge fan of Meyerhofer's poetry. His book Blue Collar Eulogies is just fantastic. But his words about Brackish gave me pause. He understands my work better than I do. And, as I Tweeted the day I read the review: it's a great thing to be read. It's a blessing to be understood. Much thanks to Michael and to the fine folks at Rain Taxi. From the review: The poems in Jeff Newberry's Brackish balance grittiness with restraint, taut imagery with dark humor. the result is an intoxicating lyrical energy about as far removed from pretension and sermonizing as one can get.

1 Comment

Guillermo Cancio-Bello reviews Brackish at The Florida Book Review: In his first book, Brackish, Jeff Newberry dredges up images of his native Northern Florida. They rise like silt in brackish water. They make shapes, tell a story, and then settle until some elusive catfish passes again. I'm humbled by such words. Much love to Lynne Barrett (Florida Book Review's founding editor) for this. Also, thank you, Guillermo Cancio-Bello, for your kind words.

I like to think that, at times, in the right light, I look a bit like one of my heroes, the poet Richard Hugo. We're both writers obsessed with place, both writers who love jazz, and both writers who see the terrain beneath our feet as a starting place, a jumping-off point, a pick-up note for poetry. Hugo's best work is improvisatory. He finds a rhythm in line one and develops a theme, like Miles Davis locked in the pocket, exploring the mode.

Hugo's work taught me that the triggering subject is the root, but the improvisation is the key. I'm nowhere near the poet was; don't misunderstand me. Rather, I see in him a kindred spirit, someone I look up to, someone who's work continues to inspire me. I'm planning a fishing trip soon. I'll look out over the Gulf of Mexico, cast a line out, and listen to the surf churning in. I'll be thinking of Richard Hugo, mourning the fact that I never got a chance to meet him. I'll try to keep this poem in my head: The Trout Richard Hugo Quick and yet he moves like silt. I envy dreams that see his curving silver in the weeds. When stiff as snags he blends with certain stones. When evening pulls the ceiling tight across his back he leaps for bugs. I wedged hard water to validate his skin- call it chrome, say red is on his side like apples in a fog, gold gills. Swirls always looked one way until he carved the water into any kinds of current with his nerve-edged nose. And I have stared at steelhead teeth to know him, savage in his sea-run growth, to drug his facts, catalog his fins with wings and arms, to bleach the black back of the first I saw and frame the cries that sent him snaking to oblivions of cress. From Making Certain it Goes On: The Collected Poems of Richard Hugo The Sundress Best of the Net online anthology is now live. Featuring some great poetry by Eduardo Corral, Elizabeth Ashe, and Wendy Xu, this year's publication features fiction by James Valvis (among others) and nonfiction by Peyton Marshall (among others). The beautiful cover image is by Rhonda Lott.

Contributing journals include Blackbird, Flycatcher: A Journal of Native Imagination, and Waccamaw: A Journal of Contemporary Literature, all perennial favorites of mine. In effect, asking what a poem is about is like asking what music is about. And our inability to answer that question succinctly is hardly a testament to the meaningless of poetry—or music for that matter. When we mistake a poem for a newspaper article or even an anecdote, then the expectations for a poem’s language changes—and drastically. As Eliot said, poetry “is a concentration, and a new thing resulting from the concentration, of a very great number of experiences which to the practical and active person would not seem to be experiences at all.” Can I get an amen?

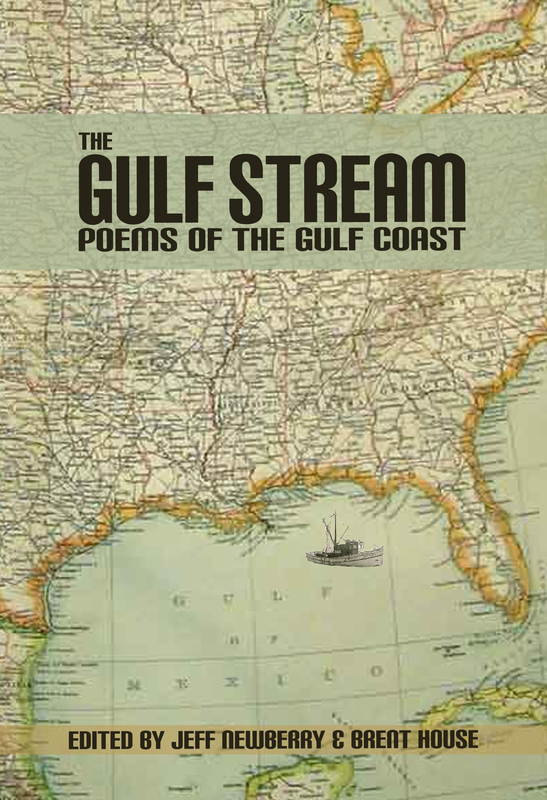

With the poet Brent House, I am editing an anthology entitled The Gulf Stream: Poems of the Gulf Coast. We are currently sending out acceptances and rejections and hope to have the book out by late spring or early summer. Much love and thanks to the fine folks at Snake~Nation~Press (especially Jean Arambula) who agreed to publish the anthology.

Below is the cover art, designed by the absolutely amazing Heather Newberry (who also did the cover for my book Brackish as well as Justin Evans' forthcoming book Hobble Creek Almanac). Thanks to Justin Evans, editor of Hobble Creek Review, I will be helping to edit a special edition of HCR focused on writers of the Gulf Coast Region. Submissions are open. HCR will also have a regular, non-Gulf Coast section, too, edited by Justin.

So, send me some work. I'm honored to be a part of Justin's vision. He's a fantastic editor and a fine poet. Check out his work here and here, and purchase his books here. I appreciate the opportunity be a part of such a great publication. Please follow all submission guidelines for Hobble Creek Review. Send Gulf Coast-related submissions to hcrgulfcoastissue@gmail.com. The following editorial statement appears on the HCR website, as well: Growing up in Port St. Joe, a tiny town on the Florida Panhandle, I hated the place. Hated the stink of the paper mill and chemical factory. Hated the tiny town’s lack of a bookstore and other amenities. Hated how isolated I felt. I wanted to escape that place; I wanted to make a life for myself somewhere else. I dreamed of New York. I dreamed of Los Angeles. I dreamed of a place far, far away, where I’d write great literature and forget that I’d come from what I thought of as Nowheresville, USA. I never made it. I attended a school close to home, the University of West Florida in Pensacola, some 150 miles west of Port St. Joe. I settled in South Georgia, where I teach writing at a small state college. The Gulf Coast is barely a three-hour drive from my house. I go as often as I can. I love to fish, and I spend a lot of time angling in the bay, the sloughs and the inlets around my hometown. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that over the years, my attitude about my hometown changed. What’s interesting to me, however, is how this change occurred. It was through my writing that I fell in love with the Gulf Coast. Reading southern writers like Larry Brown, Harry Crews, Jake Adam York, Natasha Tretheway, and a host of others inspired me. I found that my most successful writing was about the Gulf Coast. And I found that, somehow, writing about that place changed me in ways that I never anticipated. Lots of writers have a strong connection to place. One could even argue that the literary history of the United States is made up of pockets of regional writers, from the New York School to the Beat poets who migrated to San Francisco. All across the United States, writers have found their voices in the land beneath their feet. Because the Gulf resonates so strongly with me, I am honored to edit this special edition of The Hobble Creek Review. I ask that writers who have a strong connection with the Gulf Coast submit their work. You don’t have to be a Gulf Coast native, but I am looking for work that explicitly addresses to the Gulf Coast region. HCR will still be accepting regular submissions, as well, and founding editor Justin Evans will select the work for that section. Charles Wright once wrote that “All forms of landscape are autobiographical.” And I think he’s on to something. Dismissed and sneered at by certain critics, regionalism isn’t merely writing about landscape. Regional writers are smarter and far more talented than that. To write about our homes is to write about ourselves. To write about anything is to discover it all over again and, to quote another American poet, “make it new.” Forget all that you’ve learned. How many workshops taught me never to use a to be verb? That rule used to cripple me when I tried to write prose. Now, I write “was” and “is” as much as I want to. Open up a book by Faulkner and count the to be verbs. You’ll be shocked.

* For me, finding a writing place is key. Find a place, a physical location. Clear your schedule and go to that place. Sit down for an hour and write. Do not worry if the writing is any good. Just write. * Writing is not something to turn on or turn off. It happens all the time. I have my characters in my head constantly. If I’m working on a poem, I’m constantly chewing over a phrase or a word or a line break. To be a writer, think like a writer. * Read. Read everything from the classics to contemporary genre stuff. Read poetry. Read fiction. Read essays. Read a book by China Mieville. Then read a book by James Joyce. Read Hemingway. Read James Baldwin. Read Tom Franklin. Read Virginia Woolf. Read outside your genre. Poets, read fiction. Fiction writers, read poetry. Essayists, read fiction and poetry. Read challenging writing. Read writing that makes you use a dictionary. * Read and learn. Read like a writer. Ask How does this writer get away with that? * Fall in love with language. Pick favorite words. Enjoy those words. Fall in love with the sounds of words, the intrinsic rhythms of language. * Let literary theorists worry about literary theory. * Imitate the writers you love. Imitation is how all children begin to learn, and imitation is how writers begin to write. * Forget about originality. Your writing is original because you are writing it. Stereotypes emerge from half-finished work. If you tell the truth (whatever that may be and however that may appear), then your writing will be fresh and original. * Don’t worry about developing a “voice.” Your voice will emerge as you write. Despite contemporary thought that tells us the intrinsic self is a fiction, you know who you are. Your writing will sound like you eventually. * Ignore writers who tell you that you can’t or should write a certain way. Ignore writers who tell you to avoid certain subjects. Ignore anyone who tries to tell you that your writing is not important. * Readers are important, but the story or essay or poem needs to please you first. Write the kind of work you want to read. * Do not quit. Develop a damned stubborn insistence on your own writing. Harry Crews says that writing is like fishing. You have to keep a worm in the water. Do not let a day go by without casting into the water. * Writing is thinking. Just because you don’t a new chapter or a new poem every day doesn’t mean that you’re not writing. Keep your head in your work. * Care enough about your writing to discipline it. Don’t pretend that grammar rules are beneath you. If you don’t care about your writing, why on earth would you expect anyone else to? * Revision isn’t “fixing errors.” Revision is figuring out what the story/poem/essay is all about. Revision is writing. Writing is revision. * Read your own work aloud. Listen to your words. Enjoy how they feel in your mouth. Practice visceral reading: emphasize syllables as you read. Try go find the music in your writing, be it poetry or prose. * Don’t worry about writing “literature.” History will decide whether or not your work stands the test of time. * Find a community of writers, folks who understand what you’re facing. Make friends. Swap work. Understand that while writing is a lonely business, a writer doesn’t have to be a lonely soul. Nix that “suffering artist” nonsense. There’s enough suffering in the world already. I’ve been reading a lot of prose this summer: William Gay, Tom Franklin, Charles Frazier, Larry Brown, all southern novelists who have a love for the land and whose work reflects that love. I’m working on a book, myself, and I look to these writers for guidance and inspiration. And as much as I love reading their work, however, I often find myself simply overwhelmed, and I sink into this pit of self-doubt. I worry that I’ll never be as good a writer as any of these guys, and I think Why try?

This is a hard place for any writer to inhabit. On the one hand, I need the inspiration. When I study how Larry Brown seamlessly intertwines the third-person narrative voice with the character’s voice, I am driven to try something similar in my own prose. At the same time, I think, “If Brown did it this way, when why would you even try? He’s a master. You’re a journeyman, at best.” There is no easy answer here. I’m driven to imitate Brown and Gay and Franklin and Richard Hugo and Yusef Komunyakaa and numerous other writers for the same reason I imitate Slash and Buddy Guy and Stevie Ray Vaughan on guitar: the voice is one-of-a-kind; an irresistible charm comes over me when I hear it. No, I’ll never write a Larry Brown character any more than I’ll play a solo exactly as Slash does. But in my imitation, I slowly figure out my own voice, who I am on the page. Poets talk a lot about voice, but fiction writers have a voice, too, a way of writing prose that is unquestionably their own. This voice is not something slap-dash, something thrown together. No matter how “natural” it sounds, I believe that this voice emerges from the wisdom accrued through revision and failure. The more you write, the more you fail. The more you fail, the more you learn. Then, you fail again, and, to quote Samuel Beckett, you fail better. And you fail better. And you fail better again. I’m very hard on myself, and I don’t handle failure well. This probably explains why writing prose is hard for me. I’ve spent the better part of my writing career writing and reading poetry, and I think that I’ve come to some understanding of it. I am by no means a perfect poet (God, who is?), but I think I understand the genre, and I have an understanding of my own strengths and (many) weaknesses as a poet. Learning to write poetry was/is for me a process of failure, too. I have twice as many (perhaps three times as many) abandoned poems as I do successful poems. When I get frustrated writing prose (as I have been of late), it’s helpful to remember those failures that I’ve had as well as the failures that have yet to come. Whitman said “Vivas for those who have failed.” He could have been talking to writers and artists everywhere. He likely was. I’m still struggling to learn how to write prose. But I think, if there’s one thing that any successful writer has in common, it’s this: a damned, hard-headed, dogged persistence. You write, you fail, and you write again. Back to it. The page is waiting. It’s important to have people to look up to at the beginning of your career. You have to find people who have found their own way of saying the things that you yourself want to say. It never comes easy, and I believe now that it may even get harder the older you get and the more you write. The apprentice approaches the pinnacle slowly, with much stumbling and cursing, constantly going down one-way streets and taking off on tangents that go nowhere. The incredible amount of things that have to be written and then thrown away is probably what daunts a lot of young writers.

From "Harry Crews: Mentor and Friend," Billy Ray's Farm: Essays from a Place Called Tula, Touchstone-Simon & Schuster, 2001 |

O for a muse of fire, Archives

March 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed