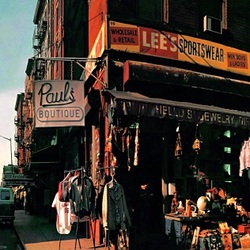

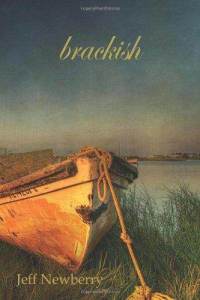

My essay "Paul's Boutique or, How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Beastie Boys" is now live over at StorySouth. Check it out. Thanks so much to Terry Kennedy and the find folks at StorySouth for publishing the essay, a reading of the album embedded in a personal reflection about my long relationship with the album. The essay is also a kind of tribute to Adam Yauch, the gravely-voiced MCA, who succumbed to cancer last year. When I heard of MCA's death, I was shocked by how much the news affected me. I've long loved hip-hop (as well as jazz, outlaw country, rock-n-roll, the blues, and a host of other musical genres), but I felt no special affinity for hip-hop. The emptiness and sorrow I felt over MCA's death forced me to write to figure out my feelings. The resulting essay taught me something about the way that I conceive of music and authenticity. I am pleased that what began as a post for this blog grew into something much more rich and c complex. I'm also happy that the essay appears in StorySouth. Way back in 2004, the late Jake Adam York published some of my poems there, one of my earliest publications. I'm honored to have been included back then, and I'm honored to see my writing in StorySouth again. This newest issue features awesome work by Richard Kraweic, John Tribble, and C.D. Mitchell. By the way, Mitchell's collection of short stories, God's Naked Will, has just been released by Burnt Bridge Press. You need to be reading this book right now. Yes, right now. Go, order a copy. Seriously. Read it.  Thanks to poet and blogger (and recently-dubbed "Doctor") Keith Montesano for interviewing me for his "First Book Interviews" blog. You can find the interview here. The interview puts me in some very good company, and I'm honored to be featured by poets as amazing as Justin Evans, Allison Pelegrin, Dan Albergotti, Jehanne Dubrow, and Gary L. McDowell. To be mentioned in the same breath as these writers is simply overwhelming. Reading their work, I'm reminded that it's an amazing time to be a writer, despite the doom and gloom we hear about the so-called "death" of the humanities. Poetry is alive and kicking, and it's so much more compelling and diverse than anyone outside of the poetry world (and many inside the poetry world) suspect. Keith's a wonderful poet in his own right. Definitely check out his debut collection, Ghost Lights, a haunting and memorable book of poetry, as well as his follow-up, the forthcoming Scoring the Silent Film, both from Dream Horse Press.  Poet, novelist, and critic Michael Meyehofer (poetry editor at Atticus Review) shows some love to Brackish in the new issue of Rain Taxi. I am very appreciative of this insightful review. I'm a huge fan of Meyerhofer's poetry. His book Blue Collar Eulogies is just fantastic. But his words about Brackish gave me pause. He understands my work better than I do. And, as I Tweeted the day I read the review: it's a great thing to be read. It's a blessing to be understood. Much thanks to Michael and to the fine folks at Rain Taxi. From the review: The poems in Jeff Newberry's Brackish balance grittiness with restraint, taut imagery with dark humor. the result is an intoxicating lyrical energy about as far removed from pretension and sermonizing as one can get. Guillermo Cancio-Bello reviews Brackish at The Florida Book Review: In his first book, Brackish, Jeff Newberry dredges up images of his native Northern Florida. They rise like silt in brackish water. They make shapes, tell a story, and then settle until some elusive catfish passes again. I'm humbled by such words. Much love to Lynne Barrett (Florida Book Review's founding editor) for this. Also, thank you, Guillermo Cancio-Bello, for your kind words.

I’ve been reading a lot of prose this summer: William Gay, Tom Franklin, Charles Frazier, Larry Brown, all southern novelists who have a love for the land and whose work reflects that love. I’m working on a book, myself, and I look to these writers for guidance and inspiration. And as much as I love reading their work, however, I often find myself simply overwhelmed, and I sink into this pit of self-doubt. I worry that I’ll never be as good a writer as any of these guys, and I think Why try?

This is a hard place for any writer to inhabit. On the one hand, I need the inspiration. When I study how Larry Brown seamlessly intertwines the third-person narrative voice with the character’s voice, I am driven to try something similar in my own prose. At the same time, I think, “If Brown did it this way, when why would you even try? He’s a master. You’re a journeyman, at best.” There is no easy answer here. I’m driven to imitate Brown and Gay and Franklin and Richard Hugo and Yusef Komunyakaa and numerous other writers for the same reason I imitate Slash and Buddy Guy and Stevie Ray Vaughan on guitar: the voice is one-of-a-kind; an irresistible charm comes over me when I hear it. No, I’ll never write a Larry Brown character any more than I’ll play a solo exactly as Slash does. But in my imitation, I slowly figure out my own voice, who I am on the page. Poets talk a lot about voice, but fiction writers have a voice, too, a way of writing prose that is unquestionably their own. This voice is not something slap-dash, something thrown together. No matter how “natural” it sounds, I believe that this voice emerges from the wisdom accrued through revision and failure. The more you write, the more you fail. The more you fail, the more you learn. Then, you fail again, and, to quote Samuel Beckett, you fail better. And you fail better. And you fail better again. I’m very hard on myself, and I don’t handle failure well. This probably explains why writing prose is hard for me. I’ve spent the better part of my writing career writing and reading poetry, and I think that I’ve come to some understanding of it. I am by no means a perfect poet (God, who is?), but I think I understand the genre, and I have an understanding of my own strengths and (many) weaknesses as a poet. Learning to write poetry was/is for me a process of failure, too. I have twice as many (perhaps three times as many) abandoned poems as I do successful poems. When I get frustrated writing prose (as I have been of late), it’s helpful to remember those failures that I’ve had as well as the failures that have yet to come. Whitman said “Vivas for those who have failed.” He could have been talking to writers and artists everywhere. He likely was. I’m still struggling to learn how to write prose. But I think, if there’s one thing that any successful writer has in common, it’s this: a damned, hard-headed, dogged persistence. You write, you fail, and you write again. Back to it. The page is waiting. I’ve spent the last few weeks furiously editing my poetry manuscript, going over each word carefully, and rearranging the book. I feel that the finished product is strong—very strong. I worry that I probably wasted a lot of money this past spring term submitting to contests, but I suppose that’s part of a writer’s life these days. I wonder how much money I’ve spent the past three years on contest fees? I don’t even want to know.

Which, of course, makes me wonder: is the contest route the only way to get a book of poetry into print anymore? Of course not. Some presses offer open reading periods. At the same time, however, many of the better small presses open their doors to unknowns (like yours truly) only during contest season. But I’m getting off track here. I wanted to write about editing and architecture, particularly the overall arc of a book of poems. The last decade has seen the publication of many books of poems that are project-oriented. I think of Tyehimba Jess’s amazing debut, Leadbelly, a biography-in-verse of the famous blues singer. I think of Kevin Young’s Black Maria, a noir-in-verse that’s well worth a read (or re-read, as it were). Books by Jake Adam York, Sabrina Mark, Sean Hill, Danielle Pafunda, and others pop to mind. I don’t know if this is something new in poetry publishing1. And I don’t want to pass a value judgment on this trend, saying whether it’s good or bad. It just is. And because it just is, I found myself looking for some kind of overarching something to hold my book together. I found it, I believe, but I don’t want to talk too much in specifics here on my blog. Suffice to say that this urge to build a book as a “project” (for lack of a better word) might spring from my love of narrative fiction. I come to poetry as a storyteller. From my earliest years, I told stories (often whopper lies to whomever would listen). When I first went to college, I wanted to be a novelist and write books and follow in the footsteps my then-heroes, Ernest Hemingway, J.D. Salinger, and Jack Kerouac. I loved narrative, then, and I still do, now. At the same time, I have a musician’s love of the lyric moment. As a guitarist, I like getting in a pocket, some blues or jazz riff, and staying there as long as I can, working the scale, working the box. I love how a writer like William Matthews does the same thing in print, occupying a moment in time and exploding it, a al John Keats. Rodney Jones does the same thing for me, though he manages to somehow be a lyric storyteller. Which is what I want my book to be: a lyric narrative. Or perhaps a narrative lyric. Or something. I think of the jazz musician’s journey, the way he sets out from the tonic note and occupies that space before returning to the dominate. Jazz is this way—the story of leaving and returning. But it’s not just the overall story of departing and coming home that interests me about jazz. It’s the journey itself, the way the soloist brings himself back home. That’s what interests me. That’s the kind of poetry I’d like to write. Recommended reading: Michael S. Harper’s Dear John, Dear Coltrane, Ed Pavlic’s Winners Have Yet to Be Announced: A Love Song for Donny Hathaway, T.R. Hummer’s The Infinity Sessions _____________________________ 1 Of course, in the end, the overarching project book isn’t new at all. See Charles Olson’s The Maximus Poems and W.C. Williams’ Paterson among many other, earlier examples. On my Facebook page a couple of days ago, I posted a little graphic that read “There is No Such Thing as Too Much Books.” I didn’t think that the picture would engender much conversation. After all, most of my online “friends” are writers; they love books, right?

Not long after I posted it, a thread had developed about book ownership. One person agreed wholeheartedly with me. Another pointed out that, ultimately, owning too many books can become like an addiction. He posted that when it got to the point in his house that he had to clear paths to his bedroom, his bathroom, and his kitchen because of stacks of books, he realized that he’d hit terminal mass. I’d never quite thought of it in that way. But my online friend is right, in a sense. Unless you live in a palatial estate, you must at some point become super-saturated with books. In my house, I have four book shelves, two seven footers (with five shelves) and two three footers (with three shelves). In my office at work, I have two shelves, a six footer with three shelves and a long six-foot one with three shelves. All of these are packed with books. I haven’t even mentioned the various literary magazines that litter my house or the unpacked boxes of books crammed into closets at home and at work. I’ve not hit terminal mass, yet. But I fear I may be close. But here’s thing: I love books. I love how they feel in my hand. I love how they smell. I love the artistry of design behind book making. I love looking at a new hardback and exploring it: has the publisher opted for a rough cut to the page? What font does the book use? How do the pages themselves feel? Glossy? Rough like old skin? Smooth? I know that I shouldn’t, but I can’t help purchasing more books. So, it’s understandable, then, that I’ve been ambivalent about ebooks since their introduction. For me, reading is more than mental; it’s visceral. Reading is physical. Reading is intimate. Though I’ve read numerous ebooks on my Kindle, I never feel as though I actually own them. I own the digital copy of the words, but I don’t own a book (I guess that assertion reveals something about the way I define book). This week, Amazon announced a Kindle lending library. Amazon Prime members can lend and borrow form other Kindle owners. I’m intrigued by the idea. I love to lend books to others, particularly my students. Inviting a person into a book is rewarding and exciting. But in lending a book, I am lending something real and tangible, not a digital copy of text. Plus, I don’t purchase enough books from Amazon to justify the nearly $80.00 a year fee that members of Amazon Prime pay. In addition, my local library (like so many others) lends digital books for free. I’ll freely admit that, in some ways, I’m not only acting a bit like a Luddite, but I’m also being hypocritical. I love my Kindle, particularly the way that a newspaper appears on it each morning. I like browsing the online Kindle bookstore. And I’ve found that on long trips, my Kindle in indispensible. I can’t tell you how many crossword puzzles I’ve worked on my Kindle. I’ve also taken chances of different kinds of literature by reading it on my Kindle. I’d probably not know about such wonderful noir and sci-fi writers like Anthony Neil Smith and D.B. Grady and Derek J. Canyon without my Kindle. So, in my reading life, I find plenty of room for an ebook reader. I’m even seriously considering purchasing a Kindle Fire. Where does this leave me, then? I love physical books, and I like ebooks a lot. The future of publishing probably lies with ebooks, particularly educational publishing (have you seen The Wasteland App? Amazing.). Ebooks are here to stay. I can’t imagine hitting terminal mass on ebooks, either. If my ebook reader gets full, I can always archive the book for later. Does that fact mean that print books will disappear? I hope not. However, to survive, traditional publishers are going to have to do what the newspaper industry did: adapt or die out. Meanwhile, I’ll continue my book collection, both digital and mortar board. At least with my ebooks, I won’t have to purchase a new bookshelf. But I’m not so sure that’s a good thing. |

O for a muse of fire, Archives

March 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed