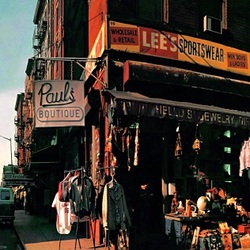

My essay "Paul's Boutique or, How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Beastie Boys" is now live over at StorySouth. Check it out. Thanks so much to Terry Kennedy and the find folks at StorySouth for publishing the essay, a reading of the album embedded in a personal reflection about my long relationship with the album. The essay is also a kind of tribute to Adam Yauch, the gravely-voiced MCA, who succumbed to cancer last year. When I heard of MCA's death, I was shocked by how much the news affected me. I've long loved hip-hop (as well as jazz, outlaw country, rock-n-roll, the blues, and a host of other musical genres), but I felt no special affinity for hip-hop. The emptiness and sorrow I felt over MCA's death forced me to write to figure out my feelings. The resulting essay taught me something about the way that I conceive of music and authenticity. I am pleased that what began as a post for this blog grew into something much more rich and c complex. I'm also happy that the essay appears in StorySouth. Way back in 2004, the late Jake Adam York published some of my poems there, one of my earliest publications. I'm honored to have been included back then, and I'm honored to see my writing in StorySouth again. This newest issue features awesome work by Richard Kraweic, John Tribble, and C.D. Mitchell. By the way, Mitchell's collection of short stories, God's Naked Will, has just been released by Burnt Bridge Press. You need to be reading this book right now. Yes, right now. Go, order a copy. Seriously. Read it.

1 Comment

Forget all that you’ve learned. How many workshops taught me never to use a to be verb? That rule used to cripple me when I tried to write prose. Now, I write “was” and “is” as much as I want to. Open up a book by Faulkner and count the to be verbs. You’ll be shocked.

* For me, finding a writing place is key. Find a place, a physical location. Clear your schedule and go to that place. Sit down for an hour and write. Do not worry if the writing is any good. Just write. * Writing is not something to turn on or turn off. It happens all the time. I have my characters in my head constantly. If I’m working on a poem, I’m constantly chewing over a phrase or a word or a line break. To be a writer, think like a writer. * Read. Read everything from the classics to contemporary genre stuff. Read poetry. Read fiction. Read essays. Read a book by China Mieville. Then read a book by James Joyce. Read Hemingway. Read James Baldwin. Read Tom Franklin. Read Virginia Woolf. Read outside your genre. Poets, read fiction. Fiction writers, read poetry. Essayists, read fiction and poetry. Read challenging writing. Read writing that makes you use a dictionary. * Read and learn. Read like a writer. Ask How does this writer get away with that? * Fall in love with language. Pick favorite words. Enjoy those words. Fall in love with the sounds of words, the intrinsic rhythms of language. * Let literary theorists worry about literary theory. * Imitate the writers you love. Imitation is how all children begin to learn, and imitation is how writers begin to write. * Forget about originality. Your writing is original because you are writing it. Stereotypes emerge from half-finished work. If you tell the truth (whatever that may be and however that may appear), then your writing will be fresh and original. * Don’t worry about developing a “voice.” Your voice will emerge as you write. Despite contemporary thought that tells us the intrinsic self is a fiction, you know who you are. Your writing will sound like you eventually. * Ignore writers who tell you that you can’t or should write a certain way. Ignore writers who tell you to avoid certain subjects. Ignore anyone who tries to tell you that your writing is not important. * Readers are important, but the story or essay or poem needs to please you first. Write the kind of work you want to read. * Do not quit. Develop a damned stubborn insistence on your own writing. Harry Crews says that writing is like fishing. You have to keep a worm in the water. Do not let a day go by without casting into the water. * Writing is thinking. Just because you don’t a new chapter or a new poem every day doesn’t mean that you’re not writing. Keep your head in your work. * Care enough about your writing to discipline it. Don’t pretend that grammar rules are beneath you. If you don’t care about your writing, why on earth would you expect anyone else to? * Revision isn’t “fixing errors.” Revision is figuring out what the story/poem/essay is all about. Revision is writing. Writing is revision. * Read your own work aloud. Listen to your words. Enjoy how they feel in your mouth. Practice visceral reading: emphasize syllables as you read. Try go find the music in your writing, be it poetry or prose. * Don’t worry about writing “literature.” History will decide whether or not your work stands the test of time. * Find a community of writers, folks who understand what you’re facing. Make friends. Swap work. Understand that while writing is a lonely business, a writer doesn’t have to be a lonely soul. Nix that “suffering artist” nonsense. There’s enough suffering in the world already. This is excerpted from a long essay I'm currently writing. Please drop me a line to tell me what you think, particularly if you have any ideas about what I should be reading/researching. I'm planning on including a section in the essay about famous marginal notes/annotations, such as Blake's annotations of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Thanks for reading. -- In college, I was a big fan of used books. A first-generation college student, I never had very much money. So, I always tried to register early. This way, I could get to the bookstore early, too. I combed the used books, looking for the best copies, the least-tarnished and annotated copies. As a freshman and sophomore, I worried what people would think about overly-abused texts. I wanted to fit in, not stand out. Plus, I wanted to be the one who wrote the formula for the quadratic equation in the margin of my algebra textbook, not some unnamed freshman who came before me. However, as I entered my upper-division courses in literature and languages, I found that my habits changed. I looked for books with annotations. I wanted the books that had copious notes written in the margins. I remember finding a well-used copy of – Romanticism anthology. That semester, I was assigned a long essay on Shelley’s “Adonais.” My tastes were distinctly 20th century. I favored Eliot and Yeats, Frost and Stevens. I found much Romantic poetry inscrutable, too concerned with flowery diction and the elevation of the self. I must confess, too, that I was a rather lazy student who hadn’t yet developed a taste for wrangling with a text and teasing out the various meanings of a poem. Whoever owned that Romanticism book before me had heavily annotated “Adonais,” and those annotations helped me as I read the poem. I read it again and again, slowly adding my own notes beneath and beside the ones that were already there. The previous owner had helped me with the poem. His or her notes provided the scaffold on which I built my own meaning. I don’t remember how well I scored on that essay (probably not too well). I do, however, remember those notes. And I remember the strange feeling that in some way, I was having a conversation with the previous owner about Shelley’s poem. As I advanced through my undergraduate days, I became an inveterate annotator. I’m ashamed to admit that at times, I even wrote in library books. I wasn’t, however, the only one who did so. I had a distinct rule: if the previous patron had annotated the book, then I felt license to do so, as well. When I did write in library books, I always used a thin-leaded mechanical pencil. In an American authors class I took under Dr. Carlos Dews at the University of West Florida, I read my way through all the required Tennessee Williams’ plays, each one a loaner from the campus library. Likely, my notes may still be in some of those books, thin, light words and thin lines joining sections of the text. Whenever I turned the books back in, I never erased the annotations. I hoped that another reader might find some use in them. Only when I began teaching as a graduate assistant did I see the true value of annotating. In writing those notes, I wasn’t merely explaining the text to myself. In the act of annotation, I was writing a new text composed of the original text and my writing. I didn’t read Tom Phillips' A Humament until much later in my scholarly life, but I think the comparison holds. Just as A Humament is a “treated” text, so the poems in the X.J. Kennedy and Dana Gioia-edited An Introduction to Poetry become my own “treatments.” I always found a lot of joy in annotating a poem. I remember sitting in the graduate student offices at the university, conferencing with students over short essays they were composing for my class. Their assignment: analyze a sonnet, paying particular attention to the way that the strict form of the poem informs the poem’s content. A young woman was sitting with me, one of my students who was completely confused about John Donne’s “Unholy Sonnet XIV,” “Batter my heart, three-personed God.” I opened my text to the poem and put my finger on the poem. “Right here,” I said, about to make what I thought was an important point about the text. “Wow,” she said. “I sure wish I had your book.” I looked down at the poem, now scored over with my own black pen (I preferred and still prefer to write in ball-point pens with fine tips). My circles and lines connected parts of the poem. My notes and half-sentences ran up and down the poem’s side. I’d circled parts of the title. My chest swelled a little with pride. This was how a professor was supposed to read. I was struck by an odd fact: the student was more impressed with my annotations than she was with Donne’s powerful words. |

O for a muse of fire, Archives

March 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed