My friend, the writer Laura Valeri, has written a thoughtful reply to Ryan Boudinot's "Things I Can Say about MFA Writing Programs Now that I No Longer Teach in One," an article that has engendered much conversation--some heated, some in agreement, some dismissive--on social media as of late. I posted the article here and on my Facebook page, too. As I said then, I don't necessarily agree with all of Boudinot's points, but I think he does raise some interesting questions for those who teach creative writing in the academy, even if those questions lead to paths that are well-trod. Nonetheless, I think this kind of debate/conversation is good for our profession, tiresome as some find it--I find the MFA-bashing tiresome, myself, for the record. Laura Valeri, "Those Who Can, Teach: A Formal Reply to Ryan Boudinot's Post on Teaching" My job [as a creative writing teacher] exists because of students who don’t read much, students who love to write but have difficulties expressing themselves, students who really want to excel and be great but are misinformed about the discipline and skills it takes to get there. We as teachers simply cannot dismiss students as “not having it” and “not being born with it” or “too late to get to it.” It’s unacceptable. If we accept them into MFA programs, take their money, and time, and hopes and dreams, then we have to make it work.

1 Comment

I do not teach in an MFA program. I didn't attend an MFA program. I did, however, complete a PhD with a focus in creative writing. I am of two minds about the critique of MFAs. On the one hand, I find the elitism and exclusivity of the AWP Industrial Complex troubling. It reduces all forms of writing to one kind. On the other hand, MFA programs have produced some remarkable writers. Further, MFA programs elevate the study of writing and emphasize some important truths about the writing life: to write well, one must read well; to write well, one needs a community of writers. So, I post this article not out of hatred for the MFA programs around the nation. I post it as food for thought. I hope that you'll read this and take a few minutes to think about it. Ryan Boudinot, "Things I Can Say about MFA Programs Now that I no Longer Teach in One" (from The Guardian)

An interesting and heated conversation took place on my Facebook page a couple of days ago after I posted this message:

Holy cow. I just some ink on a rejection from a top tier journal. Very nice. It's rare that a rejection makes me feel good, but this one did. I won’t go into the specifics of the conversation nor will I name the journal, but I will say that the vehemence and anger displayed in the conversation didn’t surprise me. There are a lot of poets writing today, and there are a lot of journals out there featuring many different kinds of aesthetics. Some poets struggle to find an audience. Other poets seem touched by the poetry gods and become well-known very quickly. I’ll be honest: it’s hard not to be jealous when I see poets whom I’ve known a long time publishing their third and fourth book and getting featured in The Southern Review, Paris Review, and Ploughshares (for example). I want that kind of readership, too. I want that kind of audience for my work. And I want the respect of my peers. [Edited to add: I ultimately want to write well-crafted poems. History can decide if they're 'great.'] Perhaps, too, I’ll confess, that I’m trying to build a career. “Careerism” is a nasty word in poetry circles. It carries a stink with it that keeps lots of artists at a distance. Indeed, some poets I’ve met even hold that to think about a “book” of poems as opposed to a single poem reveals (in me) an ugly need to be known. I disagree. There’s nothing wrong with a writer building a career. For some reasons, however, I’ve found that poets in particular bristle at this notion. The reasons are probably varied, and I can only guess at a few, and I think those reasons have something to do with money. Is poetry somehow more “pure” that prose? Does the lack of money associated with poetry indicate that the genre is somehow immune from the marketplace of ideas? Make no mistake: I do believe that capitalism hurts art. One cannot reduce a work of art to its monetary value any more than one can measure the affect a work of art has on a viewer or reader. At the same time, U.S. poets live in this system. Furthermore, many of us are academics, too, and our careers as writers are entangled (for better or for worse) with our careers as teachers. My poetry publications have a direct effect upon my teaching career—I teach composition, mainly, not creative writing (for the record). This fact sometimes troubles me—well, to be honest, this often troubles me. Still, I understand that this is how things are. However, building a writing career is most certainly not why I started writing. I started writing at first just to express myself. Like most kids, I felt strange and awkward, and writing (songs and stories at first) gave me an outlet to try to understand my place in the world. I decided to pursue writing in school because I couldn’t imagine a life that didn’t place writing at the center of what I did. And now, though my writing career has become a part of my teaching career, I don’t sit down thinking, “Okay, that tenure review is coming up. Let me compose a new poem.” I doubt any writer thinks this way. But to return to that Facebook conversation: my feelings about that rejection had nothing to do with my career as a writer or an academic. I respect that nameless journal greatly. I respect its editors and the writers who publish there. I respect its long history. I would love to be included in its pages, and the fact that the editors took a few precious moments to praise my work and invite a resubmission means a lot to me. I hate to think that the poetry world has gotten so jaded that we all scoff at the notion of publication. Good and bad writing does exist, and publication can be a kind of validation. But at the end of the day, it’s just the page and me, trying to make sense of the world, trying to make meaning with syllables. This is excerpted from a long essay I'm currently writing. Please drop me a line to tell me what you think, particularly if you have any ideas about what I should be reading/researching. I'm planning on including a section in the essay about famous marginal notes/annotations, such as Blake's annotations of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

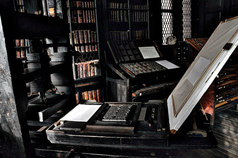

Thanks for reading. -- In college, I was a big fan of used books. A first-generation college student, I never had very much money. So, I always tried to register early. This way, I could get to the bookstore early, too. I combed the used books, looking for the best copies, the least-tarnished and annotated copies. As a freshman and sophomore, I worried what people would think about overly-abused texts. I wanted to fit in, not stand out. Plus, I wanted to be the one who wrote the formula for the quadratic equation in the margin of my algebra textbook, not some unnamed freshman who came before me. However, as I entered my upper-division courses in literature and languages, I found that my habits changed. I looked for books with annotations. I wanted the books that had copious notes written in the margins. I remember finding a well-used copy of – Romanticism anthology. That semester, I was assigned a long essay on Shelley’s “Adonais.” My tastes were distinctly 20th century. I favored Eliot and Yeats, Frost and Stevens. I found much Romantic poetry inscrutable, too concerned with flowery diction and the elevation of the self. I must confess, too, that I was a rather lazy student who hadn’t yet developed a taste for wrangling with a text and teasing out the various meanings of a poem. Whoever owned that Romanticism book before me had heavily annotated “Adonais,” and those annotations helped me as I read the poem. I read it again and again, slowly adding my own notes beneath and beside the ones that were already there. The previous owner had helped me with the poem. His or her notes provided the scaffold on which I built my own meaning. I don’t remember how well I scored on that essay (probably not too well). I do, however, remember those notes. And I remember the strange feeling that in some way, I was having a conversation with the previous owner about Shelley’s poem. As I advanced through my undergraduate days, I became an inveterate annotator. I’m ashamed to admit that at times, I even wrote in library books. I wasn’t, however, the only one who did so. I had a distinct rule: if the previous patron had annotated the book, then I felt license to do so, as well. When I did write in library books, I always used a thin-leaded mechanical pencil. In an American authors class I took under Dr. Carlos Dews at the University of West Florida, I read my way through all the required Tennessee Williams’ plays, each one a loaner from the campus library. Likely, my notes may still be in some of those books, thin, light words and thin lines joining sections of the text. Whenever I turned the books back in, I never erased the annotations. I hoped that another reader might find some use in them. Only when I began teaching as a graduate assistant did I see the true value of annotating. In writing those notes, I wasn’t merely explaining the text to myself. In the act of annotation, I was writing a new text composed of the original text and my writing. I didn’t read Tom Phillips' A Humament until much later in my scholarly life, but I think the comparison holds. Just as A Humament is a “treated” text, so the poems in the X.J. Kennedy and Dana Gioia-edited An Introduction to Poetry become my own “treatments.” I always found a lot of joy in annotating a poem. I remember sitting in the graduate student offices at the university, conferencing with students over short essays they were composing for my class. Their assignment: analyze a sonnet, paying particular attention to the way that the strict form of the poem informs the poem’s content. A young woman was sitting with me, one of my students who was completely confused about John Donne’s “Unholy Sonnet XIV,” “Batter my heart, three-personed God.” I opened my text to the poem and put my finger on the poem. “Right here,” I said, about to make what I thought was an important point about the text. “Wow,” she said. “I sure wish I had your book.” I looked down at the poem, now scored over with my own black pen (I preferred and still prefer to write in ball-point pens with fine tips). My circles and lines connected parts of the poem. My notes and half-sentences ran up and down the poem’s side. I’d circled parts of the title. My chest swelled a little with pride. This was how a professor was supposed to read. I was struck by an odd fact: the student was more impressed with my annotations than she was with Donne’s powerful words. |

O for a muse of fire, Archives

March 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed