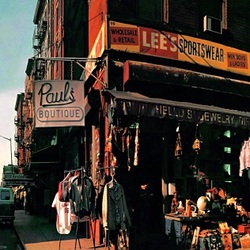

My essay "Paul's Boutique or, How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Beastie Boys" is now live over at StorySouth. Check it out. Thanks so much to Terry Kennedy and the find folks at StorySouth for publishing the essay, a reading of the album embedded in a personal reflection about my long relationship with the album. The essay is also a kind of tribute to Adam Yauch, the gravely-voiced MCA, who succumbed to cancer last year. When I heard of MCA's death, I was shocked by how much the news affected me. I've long loved hip-hop (as well as jazz, outlaw country, rock-n-roll, the blues, and a host of other musical genres), but I felt no special affinity for hip-hop. The emptiness and sorrow I felt over MCA's death forced me to write to figure out my feelings. The resulting essay taught me something about the way that I conceive of music and authenticity. I am pleased that what began as a post for this blog grew into something much more rich and c complex. I'm also happy that the essay appears in StorySouth. Way back in 2004, the late Jake Adam York published some of my poems there, one of my earliest publications. I'm honored to have been included back then, and I'm honored to see my writing in StorySouth again. This newest issue features awesome work by Richard Kraweic, John Tribble, and C.D. Mitchell. By the way, Mitchell's collection of short stories, God's Naked Will, has just been released by Burnt Bridge Press. You need to be reading this book right now. Yes, right now. Go, order a copy. Seriously. Read it.

1 Comment

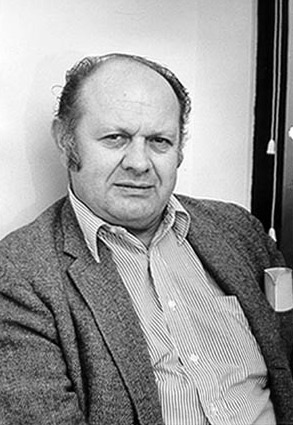

I like to think that, at times, in the right light, I look a bit like one of my heroes, the poet Richard Hugo. We're both writers obsessed with place, both writers who love jazz, and both writers who see the terrain beneath our feet as a starting place, a jumping-off point, a pick-up note for poetry. Hugo's best work is improvisatory. He finds a rhythm in line one and develops a theme, like Miles Davis locked in the pocket, exploring the mode.

Hugo's work taught me that the triggering subject is the root, but the improvisation is the key. I'm nowhere near the poet was; don't misunderstand me. Rather, I see in him a kindred spirit, someone I look up to, someone who's work continues to inspire me. I'm planning a fishing trip soon. I'll look out over the Gulf of Mexico, cast a line out, and listen to the surf churning in. I'll be thinking of Richard Hugo, mourning the fact that I never got a chance to meet him. I'll try to keep this poem in my head: The Trout Richard Hugo Quick and yet he moves like silt. I envy dreams that see his curving silver in the weeds. When stiff as snags he blends with certain stones. When evening pulls the ceiling tight across his back he leaps for bugs. I wedged hard water to validate his skin- call it chrome, say red is on his side like apples in a fog, gold gills. Swirls always looked one way until he carved the water into any kinds of current with his nerve-edged nose. And I have stared at steelhead teeth to know him, savage in his sea-run growth, to drug his facts, catalog his fins with wings and arms, to bleach the black back of the first I saw and frame the cries that sent him snaking to oblivions of cress. From Making Certain it Goes On: The Collected Poems of Richard Hugo I’ve been reading a lot of prose this summer: William Gay, Tom Franklin, Charles Frazier, Larry Brown, all southern novelists who have a love for the land and whose work reflects that love. I’m working on a book, myself, and I look to these writers for guidance and inspiration. And as much as I love reading their work, however, I often find myself simply overwhelmed, and I sink into this pit of self-doubt. I worry that I’ll never be as good a writer as any of these guys, and I think Why try?

This is a hard place for any writer to inhabit. On the one hand, I need the inspiration. When I study how Larry Brown seamlessly intertwines the third-person narrative voice with the character’s voice, I am driven to try something similar in my own prose. At the same time, I think, “If Brown did it this way, when why would you even try? He’s a master. You’re a journeyman, at best.” There is no easy answer here. I’m driven to imitate Brown and Gay and Franklin and Richard Hugo and Yusef Komunyakaa and numerous other writers for the same reason I imitate Slash and Buddy Guy and Stevie Ray Vaughan on guitar: the voice is one-of-a-kind; an irresistible charm comes over me when I hear it. No, I’ll never write a Larry Brown character any more than I’ll play a solo exactly as Slash does. But in my imitation, I slowly figure out my own voice, who I am on the page. Poets talk a lot about voice, but fiction writers have a voice, too, a way of writing prose that is unquestionably their own. This voice is not something slap-dash, something thrown together. No matter how “natural” it sounds, I believe that this voice emerges from the wisdom accrued through revision and failure. The more you write, the more you fail. The more you fail, the more you learn. Then, you fail again, and, to quote Samuel Beckett, you fail better. And you fail better. And you fail better again. I’m very hard on myself, and I don’t handle failure well. This probably explains why writing prose is hard for me. I’ve spent the better part of my writing career writing and reading poetry, and I think that I’ve come to some understanding of it. I am by no means a perfect poet (God, who is?), but I think I understand the genre, and I have an understanding of my own strengths and (many) weaknesses as a poet. Learning to write poetry was/is for me a process of failure, too. I have twice as many (perhaps three times as many) abandoned poems as I do successful poems. When I get frustrated writing prose (as I have been of late), it’s helpful to remember those failures that I’ve had as well as the failures that have yet to come. Whitman said “Vivas for those who have failed.” He could have been talking to writers and artists everywhere. He likely was. I’m still struggling to learn how to write prose. But I think, if there’s one thing that any successful writer has in common, it’s this: a damned, hard-headed, dogged persistence. You write, you fail, and you write again. Back to it. The page is waiting. I’ve spent the last few weeks furiously editing my poetry manuscript, going over each word carefully, and rearranging the book. I feel that the finished product is strong—very strong. I worry that I probably wasted a lot of money this past spring term submitting to contests, but I suppose that’s part of a writer’s life these days. I wonder how much money I’ve spent the past three years on contest fees? I don’t even want to know.

Which, of course, makes me wonder: is the contest route the only way to get a book of poetry into print anymore? Of course not. Some presses offer open reading periods. At the same time, however, many of the better small presses open their doors to unknowns (like yours truly) only during contest season. But I’m getting off track here. I wanted to write about editing and architecture, particularly the overall arc of a book of poems. The last decade has seen the publication of many books of poems that are project-oriented. I think of Tyehimba Jess’s amazing debut, Leadbelly, a biography-in-verse of the famous blues singer. I think of Kevin Young’s Black Maria, a noir-in-verse that’s well worth a read (or re-read, as it were). Books by Jake Adam York, Sabrina Mark, Sean Hill, Danielle Pafunda, and others pop to mind. I don’t know if this is something new in poetry publishing1. And I don’t want to pass a value judgment on this trend, saying whether it’s good or bad. It just is. And because it just is, I found myself looking for some kind of overarching something to hold my book together. I found it, I believe, but I don’t want to talk too much in specifics here on my blog. Suffice to say that this urge to build a book as a “project” (for lack of a better word) might spring from my love of narrative fiction. I come to poetry as a storyteller. From my earliest years, I told stories (often whopper lies to whomever would listen). When I first went to college, I wanted to be a novelist and write books and follow in the footsteps my then-heroes, Ernest Hemingway, J.D. Salinger, and Jack Kerouac. I loved narrative, then, and I still do, now. At the same time, I have a musician’s love of the lyric moment. As a guitarist, I like getting in a pocket, some blues or jazz riff, and staying there as long as I can, working the scale, working the box. I love how a writer like William Matthews does the same thing in print, occupying a moment in time and exploding it, a al John Keats. Rodney Jones does the same thing for me, though he manages to somehow be a lyric storyteller. Which is what I want my book to be: a lyric narrative. Or perhaps a narrative lyric. Or something. I think of the jazz musician’s journey, the way he sets out from the tonic note and occupies that space before returning to the dominate. Jazz is this way—the story of leaving and returning. But it’s not just the overall story of departing and coming home that interests me about jazz. It’s the journey itself, the way the soloist brings himself back home. That’s what interests me. That’s the kind of poetry I’d like to write. Recommended reading: Michael S. Harper’s Dear John, Dear Coltrane, Ed Pavlic’s Winners Have Yet to Be Announced: A Love Song for Donny Hathaway, T.R. Hummer’s The Infinity Sessions _____________________________ 1 Of course, in the end, the overarching project book isn’t new at all. See Charles Olson’s The Maximus Poems and W.C. Williams’ Paterson among many other, earlier examples. I’ve had three acceptances in the past two months, an essay to Atticus Review, and poems to both Waccamaw and The Chattahoochee Review. I couldn’t be happier. These are all fine journals, and I’m honored to be included among the fine writers they publish. No bites on my manuscript, however. Of the six or so first book contests I submitted to this year, I’ve heard back from two. The book’s still out, though, so I suppose there is hope.

It’s curious how closely my self-worth is related to publication. As an editor myself, I know what a crapshoot publication can be. Often, editors reject work not because the work is subpar (though that happens a lot), but because the journal has already accepted similar pieces. Of course, editors all have their own aesthetic tastes, as well. Writers should read journals before submitting to them. When I started doing so, my acceptance percentage definitely rose. So, rejection doesn’t have a lot to do with me personally. Still, I find myself down in the dumps after a round of stinging rejection. I suppose that will never change. *** I’m giddily excited about the new American poets U.S. postage stamps. *** The new Cortland Review is ridiculously good. With a feature on Claudia Emerson and poems by Robert Wrigley, David Kirby, David Wojan, R.S. Smith, Mark Jarman, and Kelly Cherry, the issue even features a Music Section with a video of Emerson performing a song with husband and musician Ken Ippolito and a recording of Cornelius Eady singing a song he wrote. *** On new draft this week. That totals four new poems over the past two months. Not bad, but certainly not very good, either. I’m hoping to get back to work on the novel when the spring term ends. Teaching a three courses and advising both the college’s literary magazine and its student newspaper, I have very little time to sustain the energy I need for working on prose. I can steal time here and there to work on poetry, but prose is a different story. This summer, I’ll have the time I need to sit down for a couple of hours each afternoon to write, just as I did last summer. *** Suggestions sought: name some absolute must-read books of poems that have come out in 2012. *** It's National Poetry Month. But (and equally as important, at least for me), it's also Jazz Appreciation Month. What's your favorite jazz album? For me, Miles Davis's Kind of Blue has to be one of my tops picks, but so are Coltrane's Blue Train and A Love Supreme. *** Thanks for reading. Drop some comment love below. If you like what you’ve read, why not “Like” this post on Facebook or share it on Twitter? |

O for a muse of fire, Archives

March 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed